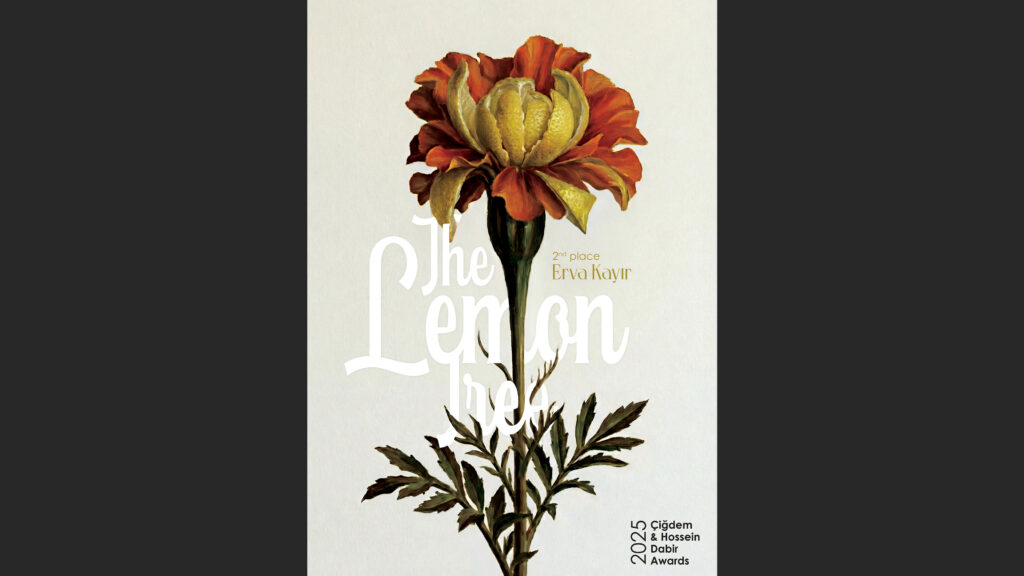

THE LEMON TREE

The house was full of chatter when I arrived. Some quietly whispered in the corners, with a

comforting hand on a shoulder. Some was full of reminiscence, tones laced with laughter and

fondness. Every room in the summer house seemed to overflow: the narrow hallway, cluttered

with too many shoes; the sunlit sitting room, thick with perfume and cologne; even the garden

door left ajar, letting in the scent of lemon and heat.

The kitchen was busy with the hustle and bustle of women. The door stood wide open,

offering a clear view of them moving quickly past with trays in hand, their voices rising over the

clatter of pots and pans. The sharp sounds of glass dishes, the soft rustle of lace doilies, and the

smell of powdered sugar and rosewater filled the air as they arranged plates of desserts to be

handed out in his honor.

Tiny bites of sweetness to soften the sour.

There was a photo of him perched up in the living room. It was one I hadn’t seen before,

set in an intricate wooden frame. Everything about it looked new and deliberate. He was smiling

in the photo, his sparse white hair curling weakly over his blotched scalp. Wrinkles, taut lines, a

beard he insisted on growing but never managed past his chin, too brittle and shallow-rooted to

reach further. Some of the liver spots were missing, as if wiped away digitally. His skin

unnaturally smooth and bright, clearly not belonging to a man who had spent his final months

circling hospitals, body failing in pieces, before suddenly dying on a dull summer night, heart

giving out under the pressure of too many surgeries packed too close together.

Someone approached me. There was pity in her eyes. I vaguely recognized her, a

neighbor, perhaps. “I’m so sorry for your loss,” she said.

“You are his granddaughter, yes?” she asked, her brows drawn together in a rehearsed

grimace of sympathy. She placed a light hand on my shoulder and gave it a slow, deliberate pat.

“Must be very hard for you. He really loved his grandchildren,” she said, glancing toward the

photo. When I remained silent, she added “May he rest in peace,” before drifting away,

muttering something under her breath with a sorrowful tone that I didn’t quite catch.

Perhaps it should have been hard for me. Perhaps it was. Perhaps I should have been

crying like my older cousin, who sat with puffy eyes and a crumpled tissue clutched tightly in

her hand. Perhaps I should have tried harder to look teary-eyed and sorrowful. Should have left

the room at the mention of his passing, sobs lodged in my throat, like my little cousin. Should

have said something—to the woman, or to all the others who stopped to offer their

condolences.

Instead, I turned away from his photo and stepped out into the garden. The lemon tree

towered over the yard, casting its shadow across the grass. I walked toward it, passing a few

people gathered on the porch. Some of them tried to talk to me. Another set of all the same

condolences, maybe a hug and some tears. All vaguely performative, they didn’t even know

him.

The lemon tree was overgrown, but looked healthy despite it all. Branches heavy with

the ripe yellow fruit, full and bright, clustered among the thick green leaves. The sun barely

leaked through. The bark, rough and solid, the trunk steady.

I heard the shuffle of feet in the grass. It was my aunt. “He’d be proud of how full it is

this year,” she said, glancing at the towering tree with fondness and reminiscence. “He cared for

it like another child,” she added, with a soft laugh.

My eyes fell to the lemons, fallen on the ground, their skin rough and dimpled. My

grandmother hunched over herself, with her bad back, collecting the fallen ones with groans

escaping her lips.

The agreement sat in my throat, unspoken.

The dinner table was laid out with the best food. A long, makeshift setup; several smaller

tables pushed together, covered in mismatched tablecloths, some silken, some floral. Plates and

plates upon food made collectively from the hands of the women who spent their entire lives in

the kitchen. And at the edge of the plates, perhaps the most sour sight, the lemonades in neat

glass cups.

“We made them from the very lemons of the lemon tree,” my aunt was saying, serving

the sour drinks in sweet cups.

We made them from the very lemons of the lemon tree, sweetened them up with loads

of sugar to mask the sour taste.

The dinner was all laughter. Reminiscence and smiles. Tears and broken faces, followed

by airy chuckles.

“He was a good man,” a man said, another neighbor. “He was generous. I’ll never forget

what he did for us when we were struggling.”

“He had a kind heart, my father,” my other aunt said, all sad smiles and shaky voices, “He

acted out of pure goodwill, nothing more. He loved all his children, his grandchildren. From the

bottom of his heart.”

“He used to take me to the park and push me on the swings, even if his knees were

frail,” My little cousin said, eyes away as if she wasn’t here but years in the past instead, “And

then we would walk to the market and he would buy me a popsicle. Everyday, after school.”

“He used to gift me books every month, it was children books but it was something,” my

older cousin said, made a small chuckle pass through the table, “He kept telling me, reading is

the most important thing. A person who reads never ends up poor.”

Everyone laughed, and I hoped it wouldn’t be my turn next. I hoped no eye on the table

would turn to me, with expectant eyes and pitying smiles. I hoped I wouldn’t be asked to tell of

the good memories I had with my grandfather.

Because there weren’t any. Because no matter how hard I tried, no matter how much I

racked my rusty brain for even a sliver of warmth with him in it, I couldn’t find it. Every memory

of him lived in the dark corners, untouched, collecting dust. I never revisited them. What was

there to reminisce about in tears and judgment?

When night began to fall and the guests drifted away, I sat with my parents on the porch.

The lemon tree stood in the distance, a quiet, looming presence. My parents spoke about my

grandfather. My mother’s eyes were teary, her voice unsteady. My father said little, his gaze

fixed somewhere far off.

They talked about him in a way that made me wonder if we were remembering the

same person. Wasn’t this the man who had made my father’s life a living hell? Why were they

so sad all of a sudden? Was I the problem?

When my father left, I finally spoke. My voice was a bit scratchy because I hadn’t said

anything the whole day except for some curtesy words. I hadn’t exactly planned the words that

left my mouth. They were an abstract thought, that finally composed itself to five clear words.

“Am I a bad person?”

My mother looked at me as if I had said the most ridiculous thing. “Of course not, honey,

why would you think that?” she said, as she leaned on her seat to hold my hand across the

table.

“I don’t know,” I said, my voice low. “Everyone talks about him as if he was this saint like

person. For people who didn’t know him, I can understand. But it’s not just the distant relatives

and neighbors and acquaintances. It’s you, too. People who have shared a roof with him, who

have visited him and saw him in the times he didn’t bother to hide his true feelings. He wasn’t a

good person, wasn’t he? Why do I feel like I am the only one that remembers?”

My mother looked down at her hands. “We remember,” she said quietly. “We haven’t

forgotten what he was like.”

“Then why are you all pretending he was something else?”

“We’re not pretending,” she said. “We’re just choosing what to hold on to now. He’s

gone. What’s left is whatever we decide to keep.”

“I can’t do that.” I said, and for the first time that whole day, my voice lodged on my

throat. It was bitter and for all the wrong reasons. “I don’t have anything good to keep. It’s like

everyone got handed a different version of him than I did.”

“Sometimes it is best to move forward from those bad memories.” My mother said, as

she squeezed my hand. “You are a good person, Goldie. I believe that you have it in your heart

to forgive him, and move on.”

I didn’t say anything. Her hand was warm. The lemonade in front of me was untouched. I

knew it would taste sweet. But all I could imagine was the sour.

When the next day came, I found myself sitting under the lemon tree. Cross-legged, the

grass prickling my legs. The sun filtered through the leaves, and I had to squint against the light.

I thought about what my mother said. About forgiving. Everyone seemed to be doing it.

Even my grandmother, who cried and cried and smoked through an entire pack of cigarettes in

her grief.

My grandmother, who had suffered the most.

A lemon fell in front of me from the tree. I picked it up. I saw my grandmother, her hands

raw, flinching as juice seeped into the cracked skin around her nails. I turned the lemon in my

palm, its skin warm from the sun. I saw her wrists straining, her knuckles taut, squeezing fruit

after fruit while his voice droned beside her. Sharp, insistent, never lifting a hand himself.

Revered for his lemonades, my grandfather. The sweet taste everyone remembered.

Drawn from her labor, sour. The sting of acid, the ache in her joints, the quiet endurance.

As I sat under the tree, I stopped trying to find a good memory. I decided to let myself

remember all the bad, all the ugly. My name was Goldie. That’s what everyone called me. He

had named me Marigold.

He liked the sound of it. Bright, delicate, proper. He imagined braids and pressed

dresses, polite smiles and folded hands. A granddaughter who sat straight at the table, who said

thank you with a soft voice, who laughed at his old jokes, even when they weren’t funny.

He didn’t like it when I started being me. He never once called me by the name I wanted.

To him, I was never Goldie, and he made sure everyone knew. He always called me Marigold,

and after a while, he stopped calling altogether. When he stopped the leers and the sneers, and

started to just look past me.

Everyone seemed to be forgiving him. Finding pieces of him to hold on to, sweetening

what they could. Maybe that made it easier.

I couldn’t. Some things were sour. They stayed sour.

I sat beneath the lemon tree, the yellow fruit resting in my palm. I tore it open with both

hands, the skin resisting at first before giving way with a sudden, wet split. Juice burst out,

spraying across my shirt, my arms, my face. It caught in my hair, dripped into my eyes. They

stung like crazy. I was crying now. That’s what everyone expected of me, wasn’t it?

I looked down at the lemon. Flesh pale and glossy, divided into clean segments, each

packed tight with trembling pulp. The juice, gathered along the edges, catching the light. Seeds

that sat lodged in the center, slick and off-white. The sharp smell of acid. I leaned forward and

bit into it.

It was incredibly sour.