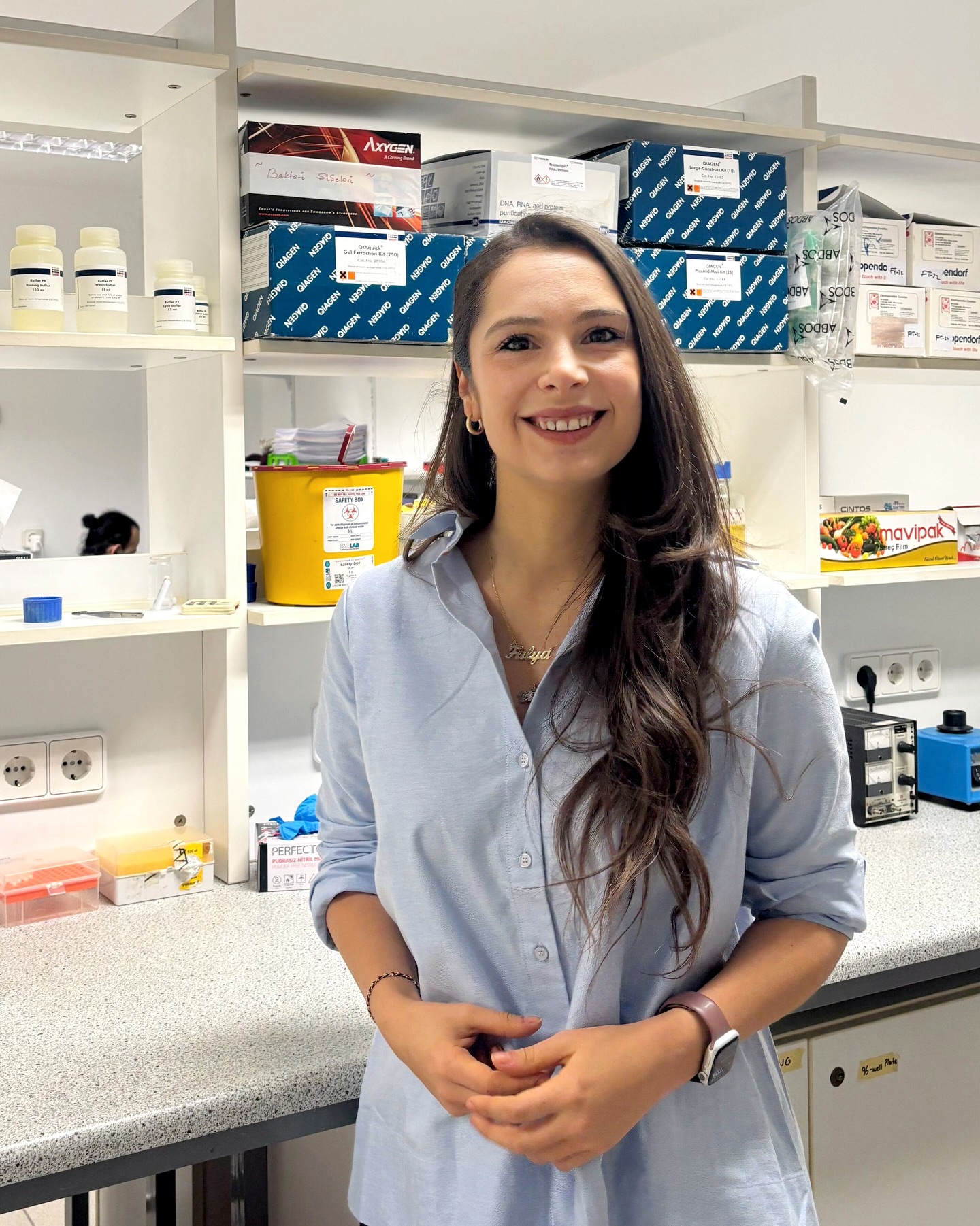

BY EKİNSU POLAT (AMER/III)

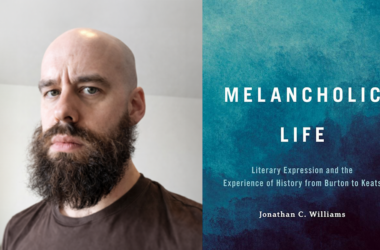

Assoc. Prof. James Alexander’s life divides into three eras: the first in Middlesbrough, a town in the north of England, where he was raised, the second in Cambridge, where he studied and eventually taught history and politics between 1991 and 2004, and the third in Bilkent, where he has taught what is usually called political theory in the Department of Political Science and Public Administration for twenty years. By “political theory” he says he means thinking about politics in terms of everything that is relevant to it: which means history, philosophy, religion, law and literature. He is teaching POLS 101 (Introduction to Political Science I) and POLS 338 (Cosmopolis: From the Roman to the Ottoman and British Empires) for the spring semester.

What has been the most exciting moment of your career so far?

When my entire theory of philosophy was accepted by a journal called “Philosophy.” It is an elegant, encompassing piece, like a poem by Eliot, or a symphony by Mahler: so I think: so he thinks. I was gratified that my own subjective sense of it was met by an objective response.

What’s one piece of information from your field that you think everyone should know?

I teach politics. I think that what everyone should know about politics is that it is bipolar to the core. It is easy: everyone understands politics. But it is difficult: it is shapeshifting and paradoxical. There is good reason why almost all the greatest philosophers in history spent at least some time thinking about it.

When and where do you do your best thinking?

It used to be after lunch, when I was a bachelor. Now that I have a family I realize that “thinking” is one half a tip-of-the-iceberg activity and one half something that almost no one ever does.

Which books have influenced you the most, and why?

Usually, I am told, the latest book I am reading. Recently I found the critical works of Thomas MacFarland in the library and thought them exceptionally good. Rene Girard was a recent discovery, too. I was unaware at first of how deeply the Bible had influenced me. At various times I have been more conscious of the influences of Bertrand Russell, Maurice Cowling, Bernard Shaw, Michael Oakeshott, R.G. Collingwood, Kierkegaard, Hegel, David Stove, Stephen Clark, Ian Robinson.

If you weren’t an academic, what career would you choose?

In some ways I am not academic. In other ways I am very academic. I dislike professionalism; I like scholarship.

If you could go back to your undergraduate/graduate student years, what advice would you give to your younger self?

This is a hard question. I was almost world-historically innocent. I thought that virtue would be rewarded. I had almost no Machiavellian intelligence. I thought the university was still what it probably had not been for more than seventy years. I am not sure the “I” giving the advice and the “I” receiving the advice would understand each other.

What do you like the most about being at Bilkent?

Bilkent is in some respects a standard university, no different from any other. In some respects, it is good. In some highly specific respects it is exceptional. I have especially valued time (no other university would have granted me so much time, and I needed time), the library and the teaching.

What’s your best work?

I have a couple of successful minor arguments but my most symphonic work is not published yet, except the above-mentioned theory of philosophy. I have an account of four fundamental logics which I doubt a journal would accept, and I have recently, at last, come up with a theory of politics.