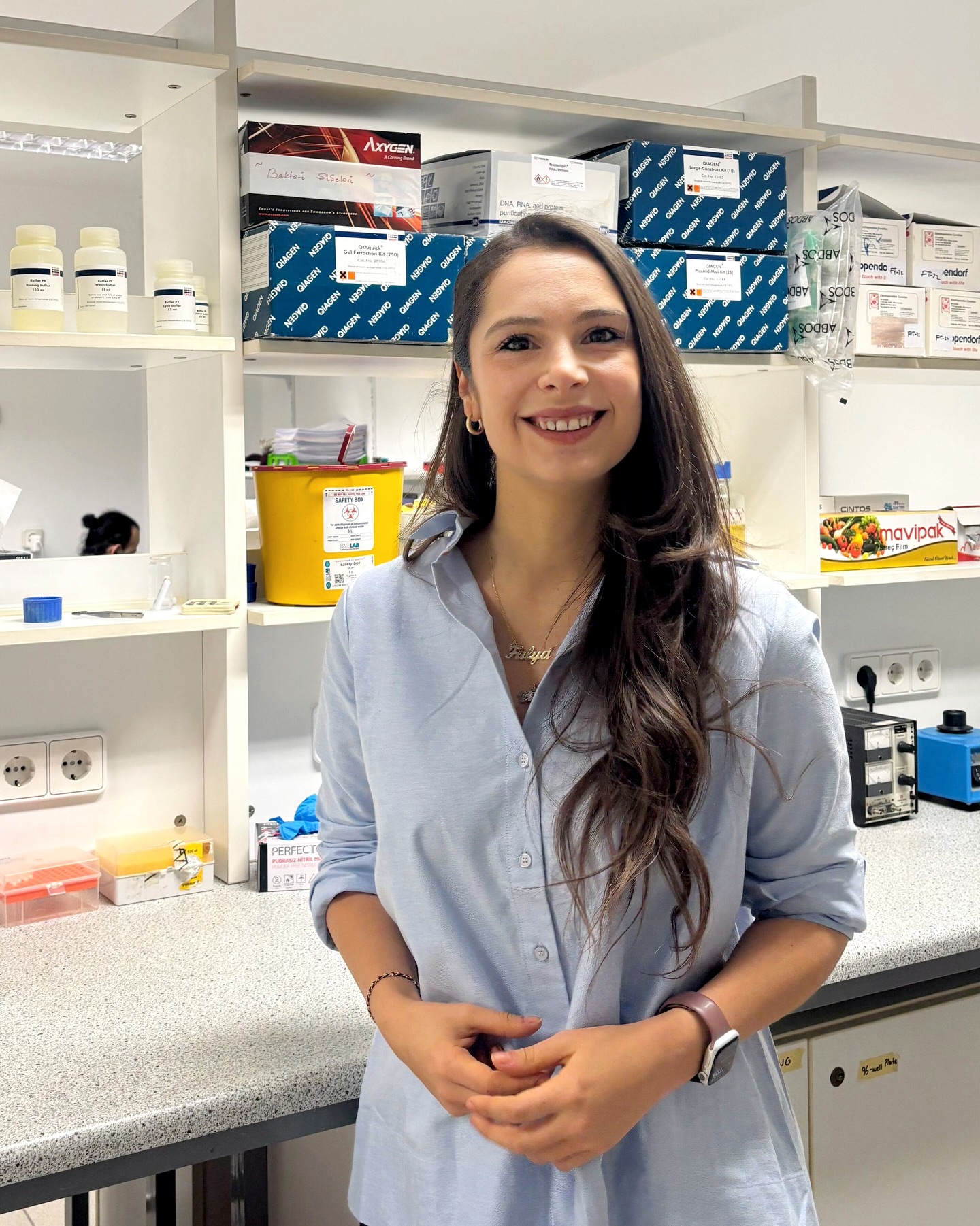

Asst. Prof. Berke Torunoğlu is a historian who specializes in the social and political history of the modern Middle East, with a particular focus on the history of the Ottoman Empire. He earned his BA in International Relations in 2006 and his MA in History in 2009, both from Bilkent University. He holds a PhD in Modern Middle East History from the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Before joining Bilkent University, Torunoğlu was a post-doctoral research fellow at the Seeger Center for Hellenic Studies at Princeton University and later served as a lecturer at the University of Tennessee-Knoxville.

Currently, Torunoğlu teaches several courses, including HIST 407/617, Ottoman Intellectual Life in the Reform Period (1839–1914); HIST 442/702, and A History of the Modern Middle East (1800 to Present).

Why did you choose an academic career?

I’m a curious person by nature.

I do it for myself. I’m deeply curious about everything under the sun. I want to have at least a basic understanding of everything.

I could have been a physicist. So, why history? I felt that humankind is the most interesting subject to study. I chose history because I believed it was the most concrete of the social sciences I could pursue.

This is what I initially thought, but then I realized that history is as imagined as psychology and as fluid. So, I ended up in this life, which is a somewhat selfish attempt to satisfy my curiosity.

What has been the most exciting moment of your career so far?

A defining moment for me was when, as an undergraduate, I took a seminar with the late Professor Halil İnalcık. I was in my fourth year and didn’t really know what I was getting into, but we were reading historical documents, and I realized there’s something called a “meta-text.” It’s not just words on paper—it’s the intentionality, the unspoken messages conveyed through phraseology and the structure of the text. That opened my eyes to the idea that our means of communication, whether through language or written text, is flawed. That realization changed how I view everything, from media to casual conversations. It was a turning point for me and made me want to become a historian.

What’s one piece of information from your field that you think everyone should know?

I’ll go with the first thing that pops into my mind, related to the course I’m offering right now. It’s about the Committee of Union and Progress (CUP). There are two distinct CUPs. When we refer to İttihatçılar, we often mean the military wing in Salonica, but we should also recognize the intellectuals in Europe. These two groups were segregated for a long time.

When and where do you do your best thinking?

Usually, in my lojman, surrounded by my cats. I tend to do my best thinking late at night. You know the term “eşref saati”? Well, my eşref saati is probably around 10 p.m. and onwards. It’s not great for my health and well-being, but I’ve made my peace with it.

What distracts you?

I distract myself. As I mentioned earlier, this is a selfish crusade to satisfy my curiosity. Sometimes, I’ll spend days reading about topics that have nothing to do with my research, like the Spanish painter Goya and his impressions of the Napoleonic armies. I have no intention of researching or publishing about it, but I’ll dive deep into it for days.

What are you most curious about?

As I’ve I said, I’m curious about everything under the sun—anything humans have done, from architecture to culinary activities. It’s hard to say what I’m most curious about because it changes based on my mood or some serendipitous event. Suddenly, something will catch my attention, and I’ll get invested in it.

What do you like to do when you are not working?

I feel like I’ve really neglected my literary reading. I’ve been trying to focus on reading literature to appreciate another aspect of human achievements.

If you weren’t an academic, what career would you choose?

I was very close to becoming an archaeologist. It’s quite similar to history. Then I realized that I’d have to spend my summers outdoors, under the hot sun, whereas in academia I get to stay indoors with air conditioning and work in front of my computer.

I’m still interested in archaeology, and I can imagine a version of myself as an archaeologist.

What is the secret of leading a happy life?

Good food, good sleep—I’ll give you the “old man” answers.

Happiness, I don’t think, is a constant. It’s a state of mind, something fleeting that we chase. So, I’ll let you know when I find the answer!

I think you can be happy after enjoying a good meal for five minutes. Then you realize you might gain weight, and your happiness fades. So, I think happiness is about increasing those small moments of joy.

If you could go back to your undergraduate/graduate student years, what advice would you give to your younger-self?

Learn Russian earlier. Invest in your health—work out. Definitely learn a third language as early as possible and read more literature. Don’t be intimidated by Russian novelists who write 2,000-page books. Finish Tutunamayanlar, for example.

What do you like the most about being at Bilkent?

Bilkent is my alma mater, so I already had a very high opinion of it. All my role models were Bilkent professors, so I feel like I’m living the dream. That’s one reason.

Another reason is that I’m an Ottoman historian and of all the disciplines in the sciences, this is the one most centered in Turkey. You can’t say that physics, for example, is centered in any one place—it’s global. But for Ottoman history, the archives, the architecture, the documents and the culture are all here in Turkey. So, I feel like I’m exactly where I need to be to do my job well.

What projects are you working on currently?

One article I’m working on is about Ottoman-Greek relations during the Crimean War. It’s a rather dry topic about an undeclared war that culminated in the deportation of some Greek nationals and some border skirmishes—events that I realized had not been thoroughly explored in the scholarship.

What excites you about your work? What’s the coolest thing about it?

The coolest thing about my work? I’ll give you an anecdote: I think the coolest part is being in physical contact with the historical documents that people read about in books. For example, I can read the actual handwriting of a sultan, complete with his notes in the margins. Sometimes I open an envelope from the Ottoman archives that’s still sealed and occasionally gold dust falls out. The gold dust was used to dry the ink, especially for fancy correspondences. Once when I opened an envelope, gold dust fell onto my lap—probably worth more than my graduate student salary at the time!

I think that’s very cool. If you’re curious about the world you live in, this is one of the coolest things you can do. It’s about understanding what humans have done—history is the record of human achievement. As a human being, there’s nothing cooler than studying what our kind has accomplished in the past.

What is your best work, in your opinion?

I tend to cringe when I read my own work, but I think that’s normal. I see it as a good sign. If you think you’ve done your best and it’s the best you’ll ever do, then there’s no room for growth.

I guess I’m proud of the work I put into my dissertation, considering that it involved researching multiple archives—from British to Russian to Ottoman to Greek. I can’t even imagine how I managed the mental and physical effort required for that 10 years ago. I don’t think I could do it now.

Which books have influenced you the most and why?

That’s a tough question, but I really, really like Şerif Mardin’s The Genesis of the Young Ottoman Thought. It’s not the best-written or the most well-researched book, but it came to me at a certain point in my life when I found it fascinating. It led me to learn about the Tanzimat reformers, Islam as a culture and a way of thinking, modernity and westernization.

This work influenced me so much that it was one of the reasons I learned Ottoman Turkish; I wanted to feel as smart as Şerif Mardin. He became a role model for me.

What’s the most common misconception about your work?

The most common misconception is that history is a “done deal.” People assume it has already happened so there’s nothing new a historian can do other than repeat what past historians have said. But that’s not the case.

First, people lie—that’s a given. Second, our interpretation of history, our vision and our methodology have changed over time. Today, we use comparative methods, and we’re only beginning to understand how humankind has thought and collected their documents.

Another misconception is that history is one of the oldest disciplines. In reality it only became a formal discipline in the mid-19th century, emerging from philology. The early historians appeared in Europe in the late 19th century. So, it’s a relatively new field.

Something that is a bit self-deprecating is that since history was created as a discipline, it can also be unmade. It’s possible that in a generation or two, history as we know it may not exist. Maybe computer scientists, through data analysis, will be the best historians of the future.

If you had unlimited funds, what would you like to do in research or in projects?

I would invest heavily in digital humanities. Specifically, I’d work to digitize and make all the Ottoman documents searchable and, ideally, even readable, by transliterating them into modern Turkish.

So, with unlimited funds, I’d probably continue doing what I’m doing right now—just with more resources and confidence.